- 1. Getting Started

-

2.

First Semester Topics

-

General Chemistry Review

- Introduction

- Electron Configurations of Atoms

- QM Description of Orbitals

- Practice Time - Electron Configurations

- Hybridization

- Closer Look at Hybridization

- Strategy to Determine Hybridization

- Practice Time! - Hybridization

- Formal Charge

- Practice Time - Formal Charge

- Acids-bases

- Practice Time - Acids and Bases

- Hydrogen Bonding is a Verb!

- Progress Pulse

-

Structure and Bonding

- Chemical Intuition

- From Quantum Mechanics to the Blackboard: The Power of Approximations

- Atomic Orbitals

- Electron Configurations of Atoms

- Electron Configurations Tutorial

- Practice Time - Structure and Bonding 1

- Lewis Structures

- Drawing Lewis Structures

- Valence Bond Theory

- Valence Bond Theory Tutorial

- Hybridization

- Polar Covalent Bonds

- Formal Charge

- Practice Time - Structure and Bonding 2

- Curved Arrow Notation

- Resonance

- Electrons behave like waves

- MO Theory Intro

- Structural Representations

- Progress Pulse

-

Acids/Base and Reactions

- Reactions

- Reaction Arrows: What do they mean?

- Thermodynamics of Reactions

- Acids Intro

- Practice Time! Generating a conjugate base.

- Lewis Acids and Bases

- pKa Scale

- Practice Time! pKa's

- Predicting Acid-Base Reactions from pKa

- Structure and Acidity

- Structure and Acidity II

- Practice Time! Structure and Acidity

- Curved Arrows and Reactions

- Nucleophiles

- Electrophiles

- Practice Time! Identifying Nucleophiles and Electrophiles

- Mechanisms and Arrow Pushing

- Practice Time! Mechanisms and Reactions

- Energy Diagrams and Reactions

- Practice Time! - Energy Diagrams

- Progress Pulse

- Introduction to Retrosynthesis

-

Alkanes and Cycloalkanes

- Introduction to Hydrocarbons and Alkanes

- Occurrence

- Functional Groups

- Practice Time! Functional Groups.

- Structure of Alkanes - Structure of Methane

- Structure of Alkanes - Structure of Ethane

- Naming Alkanes

- Practice Time! Naming Alkanes

- Alkane Isomers

- Relative Stability of Acyclic Alkanes

- Physical Properties of Alkanes

- Ranking Boiling Point and Solubility of Compounds

- Conformations of Acyclic Alkanes

- Practice Time! Conformations of acyclic alkanes.

- Conformations of Cyclic Alkanes

- Naming Bicyclic Compounds

- Stability of Cycloalkane (Combustion Analysis)

- Degree of Unsaturation

-

Stereochemistry

- Enalapril in ACE

- Constitutional and Stereoisomers

- Chirality or Handedness

- Drawing a Molecules Mirror Image

- Exploring Mirror Image Structures

- Enantiomers

- Drawing Enantiomers

- Practice Time! Drawing Enantiomers

- Identifying Chiral Centers

- Practice Time! Identifying Chiral Molecules

- CIP (Cahn-Ingold-Prelog) Priorities

- Determining R/S Configuration

- Diastereomers

- Meso Compounds

- Fischer Projections

- Fischer Projections: Carbohydrates

- Measuring Chiral Purity

- Practice Time! - Determining Chiral Purity and ee

- Chirality and Drugs

- Chiral Synthesis

- Prochirality

- Converting Fischer Projections to Zig-zag Structures

- Practice Time! - Assigning R/S Configurations

-

Alkenes and Addition Reactions

- The Structure of Alkenes

- Alkene Structure - Ethene

- Physical Properties of Alkenes

- Naming Alkenes

- Health Insight - BVO (Brominated Vegetable Oil)

- E/Z and CIP

- Stability of Alkenes

- H-X Addition to Alkenes: Hydrohalogenation

- Practice Time - Hydrohalogenation

- X2 Addition to Alkenes: Halogenation

- HOX addition: Halohydrins

- Practice Time - Halogenation

- Hydroboration/Oxidation of Alkenes: Hydration

- Practice Time - Hydroboration-Oxidation

- Oxymercuration-Reduction: Hydration

- Practice Time - Oxymercuration/Reduction

- Oxidation and Reduction in Organic Chemistry

- Calculating Oxidation States of Carbon

- Identifying oxidation and reduction reactions

- Practice Time - Oxidation and Reduction in Organic

- Oxidation

- Reduction

- Capsaicin

-

Alkynes

- Structure of Ethyne (Acetylene)

- Naming Alkynes

- Practice Time! - Naming Alkynes

- Physical Properties of Alkynes

- Preparation of Alkynes

- Practice Time! - Preparation of Alkynes

- H-X Addition to Alkynes

- X2 Addition

- Hydration

- Reduction of Alkynes

- Practice Time! - Addition Reactions of Alkynes

- Oxidative Cleavage of Alkynes

- Alkyne Acidity and Acetylide Anions

- Reactions of Acetylide Anions

- Retrosynthesis Revisted

- Practice Time! - Multistep Synthesis Using Acetylides

-

Alkyl Halides and Alcohol

- Naming Alkyl Halides

- Naming Alcohols

- Classes of Alcohols and Alkyl Halides

- Practice Time! - Naming Alkyl Halides

- Practice Time! - Naming Alcohols

- Physical Properties of Alcohols and Alkyl Halides

- Structure and Reactivity of Alcohols

- Structure and Reactivity of Alkyl Halides

- Preparation of Alkyl Halides and Tosylates from Alcohols

- Practice Time! - Alcohols to Alkyl Halides

- Preparation of Alkyl Halides from Alkenes; Allylic Bromination

- Strategy for Predicting Products of Allylic Brominations

- Practice Time! - Allylic Bromination

-

Substitutions (SN1/SN2) and Eliminations (E1/E2)

- Introduction

- Solvents

- SN1 Reaction: The Carbocation Pathway

- SN2 Reactions: The Concerted Backside Attack

- SN1 vs. SN2: Choosing the Right Path

- Application: Cardura (Doxazosin)

- E1 Reactions: Elimination via Carbocations

- E2 Reactions: The Concerted Elimination

- E1cB: The Conjugate Base Elimination Pathway

- Substitution versus Elimination

- Dienes, Allylic and Benzylic systems

-

General Chemistry Review

-

3.

Second Semester Topics

- Arenes and Aromaticity

-

Reactions of Arenes

- Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution

- EAS-Halogenation

- EAS-Nitration

- Practice Time - Synthesis of Aniline

- EAS-Alkylation

- Practice Time - Friedel Crafts Alkylation

- EAS-Acylation

- Practice Time - Synthesis of Alkyl Arenes

- EAS-Sulfonation

- Practice Time - EAS

- Donation and Withdrawal of Electrons

- Regiochemistry in EAS

- Practice Time - Directing Group Effects

- Synthesizing Disubstituted Benzenes: Effects of Substituents on Rate and Orientation

- Steric Considerations

- Strategies for Synthesizing Disubstituted Benzenes

- NAS - Addition/Elimination

- NAS - Elimination/Addition - Benzyne

- Alcohols and Phenols

-

Ethers and Epoxides

- Intro and Occurrence

- Crown Ethers and Cryptands

- Preparation of Ethers

- Reactions of Ethers

- Practice Time - Ethers

- Preparation of Epoxides

- Reactions of Epoxides - Acidic Ring Opening

- Practice Time - Acidic Ring Opening

- Reactions of Epoxides - Nucleophilic Ring Opening

- Practice Time - Nucleophilic Ring opening

- Application - Epoxidation in Reboxetine Synthesis

- Application - Nucleophilic Epoxide Ring Opening in Crixivan Synthesis

- Physical Properties of Ethers and Epoxides

- Naming Ethers and Epoxides

-

Aldehydes and Ketones

- Naming Aldehydes and Ketones

- Physical Properties of Ketones and Aldehydes

- Practice Time - Naming Aldehydes/Ketones

- Nucleophilic addition

- Addition of Water - Gem Diols

- Practice Time - Hydration of Ketones and Aldehydes

- Addition of Alcohols - Hemiacetals and Acetals

- Acetal Protecting Groups

- Hemiacetals in Carbohydrates

- Practice Time - Hemiacetals and Acetals

- Addition of Amines - Imines

- Addition of Amines - Enamines

- Practice Time - Imines and Enamines

- Application - Imatinab Enamine Synthesis

- Addition of CN - Cyanohydrins

- Practice Time - Cyanohydrins

- Application - Isentress Synthesis

- Addition of Ylides - Wittig Reaction

- Practice Time - Wittig Olefination

- Structure of Ketones and Aldehydes

- Carboxylic Acids and Derivatives

- Enols and Enolates

- Condensation Reactions

-

4.

NMR, IR, UV and MS

- Spectroscopy

-

HNMR

- Nuclear Spin

- Interpreting

- Chemical Shift

- Practice Time! - Chemical Shift

- Equivalency

- Indentifying Homotopic, Enantiotopic and Diastereotopic Protons

- Practice Time! - Equivalency

- Intensity of Signals

- Spin Spin Splitting

- Practice Time! - Spin-Spin Splitting

- Primer on ¹³C NMR Spectroscopy

- Alkanes

- Alkynes

- Alcohols

- Alkenes

- Coupling in Cis/Trans Alkenes

- Ketones

- HNMR Practice 1

- HNMR Practice 2

- HNMR Practice 3

- HNMR Practice 4

- Exchangeable Protons and Deuterium Exchange

- IR - Infrared Spectroscopy

- UV - Ultraviolet Spectroscopy

- Mass Spectrometry

-

5.

General Chemistry

- General Chemistry Lab

- Strategy for Balancing Chemical Reactions

- Calculator Tips for Chemistry

- Significant Figures

- Practice Time! Significant Figures

- Spreadsheets - Getting Started

- Spreadsheets - Charts and Trend lines

- Standard Deviation

- Standard Deviation Calculations

- Factor Labels

- Practice Time! - Factor Labels

- Limiting Reagent Problem

- Percent Composition

- Molar Mass Calculation

- Average Atomic Mass

- Empirical Formula

- Practice time! Empirical and Molecular Formulae

- Initial Rate Analysis

- Practice Time! Initial Rate Analysis

- Solving Equilibrium Problems with ICE

- Practice Time! Equilibrium ICE Tables

- Le Chatelier's

- Practice Time! Le Chatelier's Principle

- 6. Organic Chemistry Lab

- 7. Tools and Reference

-

8.

Tutorials

- Reaction Mechanisms (introduction)

- Factor Labels

- Acetylides and Synthesis

- Drawing Cyclohexane Chair Structures

- Drawing Lewis Structures

- Aromaticity Tutorial

- Common Named Aromatics (Crossword Puzzle)

- Functional Groups (Flashcards)

- Characteristic Reactions of Functional Groups

- Alkyl and Alkenyl Groups

- Valence Bond Theory

- Alkane Nomenclature

-

9.

The Alchemy of Drug Development

- Ivermectin: From Merck Innovation to Global Health Impact

- The Fen-Phen Fix: A Weight Loss Dream Turned Heartbreak

- The Asymmetry of Harm: Thalidomide and the Power of Molecular Shape

- Semaglutide (Ozempic): From Lizard Spit to a Once-Weekly Wonder

- From Cocaine to Novocain: The Development of Safer Local Anesthesia

- The Crixivan Saga: A Targeted Strike Against HIV

- The story of Merck’s COX-2 inhibitor, Vioxx (rofecoxib)

- The Accidental Aphrodisiac: The Story of Viagra

- THC: A Double-Edged Sword with Potential Neuroprotective Properties?

- Ritonavir Near Disaster and Polymorphism

- 10. Allied Health Chem

Clear History

Introduction to Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy

The light our eyes perceive is only a small portion of a much broader spectrum of electromagnetic radiation. This spectrum ranges from high-energy gamma rays and X-rays to low-energy radio waves. On the high-energy side of the visible spectrum lies the ultraviolet (UV) region, while on the low-energy side lies the infrared (IR) region. The infrared region, in particular, is of great importance in chemistry because it corresponds to the energy required to excite molecular vibrations.

The portion of the infrared spectrum most useful for analyzing organic compounds is not immediately adjacent to the visible region but spans wavelengths from 2,500 to 16,000 nm (nanometers). This corresponds to a frequency range of approximately 1.9 × 10¹³ to 1.2 × 10¹⁴ Hz (hertz). While these values are scientifically accurate, they are cumbersome to work with in practice. For this reason, chemists typically use wavenumber (expressed in cm⁻¹), which is the reciprocal of wavelength and is directly proportional to energy. The wavenumber scale for the IR region most relevant to organic compounds ranges from 400 to 4,000 cm⁻¹, making it a more convenient and intuitive unit for interpreting IR spectra.

Molecules vibrate and rotate in three dimensions at various discrete frequencies. Non-linear molecules have 3N–6 normal vibrational modes, where N is the number of atoms in the molecule. For example, methane (CH₄) has 3(5)-6 = 9 normal vibrational modes. The more atoms a molecule has, the more complex its vibrational spectrum becomes. These vibrations arise from different types of motions, such as stretching and bending. For methane, some of the important vibrational modes include C–H stretching and bending, as illustrated in the next page.

Why 3N–6?

Each atom in a non-linear molecule can move in three dimensions (x, y, z), hence the 3N term. However, if every atom in the molecule moves in the same direction (e.g., the x-direction), this corresponds to a translation of the entire molecule rather than an internal vibration. Therefore, we subtract 3 to account for translations in the x, y, and z directions. Additionally, we subtract another 3 to account for rotations about the x, y, and z axes. This leaves us with 3N–6 normal vibrational modes for non-linear molecules.

For linear molecules, the situation is slightly different. A linear molecule has 3N–5 vibrational modes. Can you explain why? (Hint: Think about how rotations differ in a linear molecule compared to a non-linear one.)

Infrared Radiation (IR) and Vibrational Spectroscopy

The vibrational modes of molecules have quantized energy levels, meaning they vibrate at specific frequencies. When a molecule is exposed to infrared radiation of the appropriate frequency, it can absorb photons, causing its vibrational modes to transition to higher energy levels. The energy differences between these vibrational states correspond to the energy of infrared radiation, which is why IR spectroscopy is often referred to as vibrational spectroscopy.

IR spectroscopy is a powerful tool for identifying functional groups in organic molecules. Each functional group has characteristic vibrational frequencies that appear as peaks in the IR spectrum. For example, the C–H stretching vibrations of an sp²-hybridized carbon (such as in benzene) typically appear around ~3300 cm⁻¹. To explore this further, use the interactive animation of benzene's vibrational modes. Select the frequency corresponding to the C(sp²)–H stretching mode to visualize how the molecule vibrates at this energy.

By analyzing the IR spectrum of a molecule, chemists can identify the presence of specific functional groups and gain insight into the molecular structure. As you progress through this chapter, you will learn how to interpret IR spectra and correlate vibrational frequencies with molecular features.

Benzene Vibrations

Transmission and Absorption Spectra

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy exploits the interaction of infrared radiation with molecular vibrations. When IR light is passed through a sample, certain frequencies are absorbed by the molecule, corresponding to specific vibrational modes. The remaining light is transmitted. IR spectra can be recorded in two primary modes: transmission and absorption.

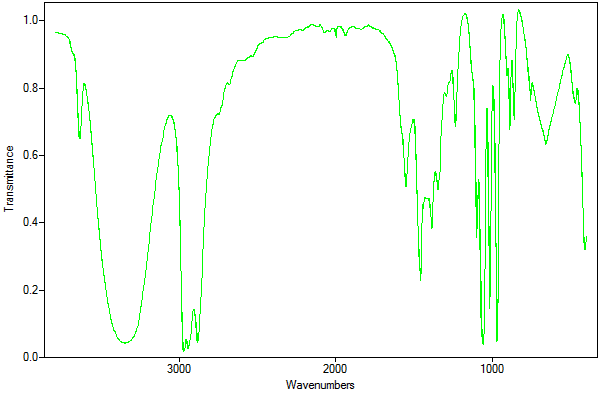

- Transmission IR: Measures the amount of IR light that passes through the sample. Peaks in a transmission spectrum correspond to lower transmittance (less light passing through), indicating absorption. For example, the following is the Transmission IR spectrum for 1-propanol

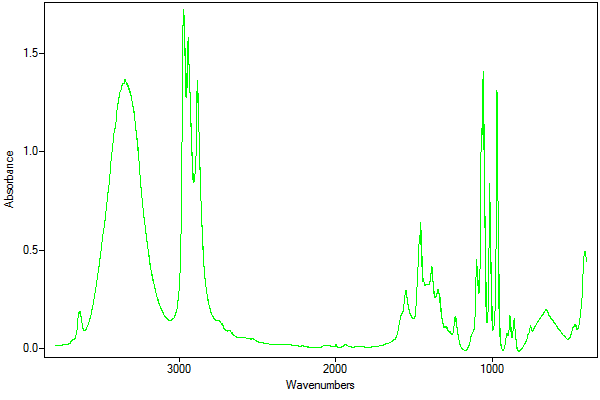

- Absorption IR: Directly measures the amount of IR light absorbed by the sample. Peaks in an absorption spectrum correspond to higher absorbance, indicating stronger absorption. While both modes provide the same fundamental information, absorption spectra are often preferred for quantitative analysis due to their linear relationship with concentration. For example, the following is the absorption IR spectrum for 1-propanol