Quick Menu

Essential Ideas

Tips for Success

A few things to help yourself …

- Attend lectures

- Ask questions when you need clarification

- Read the material

- Practice problems from chapters and self-check answers with the book’s answer keys

- Keep up with your assignments & quizzes

- Group study & take advantage of help resources

- Until the first exam, I don’t know how well you’re ‘getting’ the material unless YOU tell me … if you’re not asking questions, then I assume you understand

Chemistry in Context

Phases & Classification of Matter0

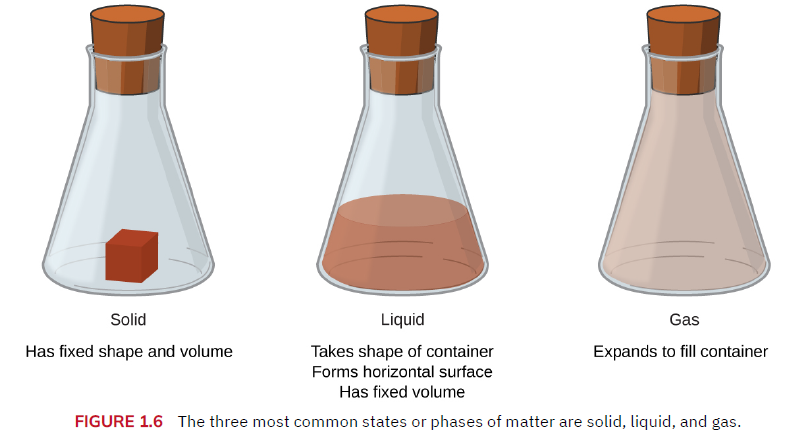

Matter – any thing that has mass and volume (i.e., takes up space), such as an atom (very tiny), a human, or a planet.

The three phases of matter are solids, liquids and gases. Note: A plasma is sometimes considered a 4th phase.

Mass vs. Weight –

Mass = amount of matter in an object (a scaler quantity - only has magnitude)

Weight = mg (a vector quantity - i.e. a force - depend on gravity)

Where

g=acceleration due to gravity

m=mass

Law of Conservation of Matter – matter cannot magically appear or disappear; it can only change into something else.

- If you ate breakfast this morning, the mass of that breakfast is the sum total of all the atoms/molecules you consumed. Once those enter the body, they get rearranged and used up in chemical reactions to provide energy, provide stored energy for later, or get flushed through your system.

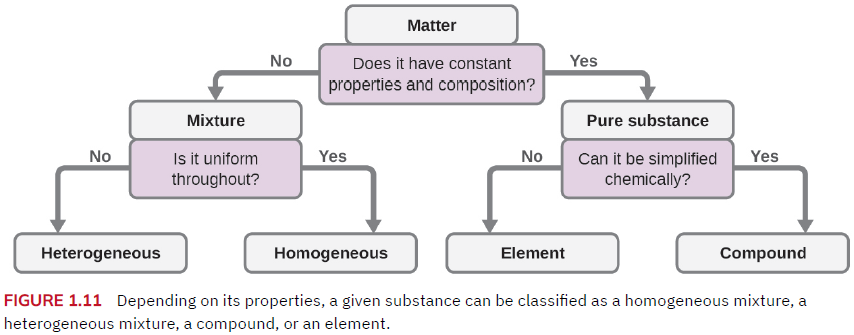

Classifying matter

- Pure substance … material with a constant composition such as elements and compounds

- Element – a pure substance that cannot be further broken down; the smallest unit of an element is the atom. All known elements are organized on the Periodic Table

- Compound – a pure substance that consists of two or more atoms bonded together in a specific ratio which can be broken down by chemical change into other atoms/compounds. Simple compounds include water (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and oxygen gas (O2); whereas complex compounds can have thousands of atoms in their chemical formula (such as proteins).

Classifying matter

- Mixture – two or more types of matter present in varying amounts (not bonded together) that can be separated by physical changes. Saline is a mixture of water and salt (NaCl) but if one boils away the water, the salt remains.

- Heterogeneous mixture – a mixture in which the individual components are distinguishable, such as trail mix, Italian salad dressing, granite, and the paper used in US currency.

- Homogeneous mixture (aka solution) – a mixture in which the individual components are NOT distinguishable such as saline solution, Gatorade, maple syrup, gasoline, or a piece of stainless steel.

- A solution contains a solvent (the majority component) and one or more dissolved solutes (the minority component[s]).

The smallest particle of an element (pure substance) that has the properties of that element is the atom.

- A pure gold rings contains a huge amount of gold atoms (Au).

- A balloon filled with pure helium gas (He) contains a huge amount of He atoms.

- Helium atoms and gold atoms are nothing alike, with different physical and chemical properties.

- Atoms are small … a ½ L soda bottle filled with pure helium gas would contain roughly 1.3 x 1022 He atoms. That’s about 13,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 He atoms.

Preview: Atoms are made of three types of subatomic particles:

- Proton – a positive particle (+1) located in the nucleus

- Neutron – a neutral particle located in the nucleus

- Electron - a negative particle (-1) located outside the nucleus

The number of protons in an atom define its identity.

- A hydrogen (H) atom contains 1 proton

- A carbon (C) atom contains 6 protons

- A gold (Au) atom contains 79 protons

- A uranium (U) atom contains 92 protons

A proton is a proton is a proton … but a hydrogen atom is not a carbon atom or not a uranium atom. This same concept applies to neutrons and electrons.

A molecule is made of two or more atoms that are bonded together in a fixed way – the number of and types of atoms (elements) AND HOW they are connected in 3-D space define the molecule’s identity.

A chemical formula is a shorthand notation way of writing the number of and types of atoms (elements) in the molecule.

- A water molecule contains 2 hydrogens and 1 oxygen: H2O

- A carbon dioxide molecule contains 1 carbon and 2 oxygens (CO2) while carbon monoxide contains 1 carbon and 1 oxygen (CO) … although both have carbon and oxygen, they have a different ration and connection and are therefore NOT the same compound (molecule).

Some molecules consist of only one atom (element) type, such as diatomic gases: oxygen (O2), nitrogen (N2), chlorine (Cl2); or the natural (elemental) state of sulfur (S8) or phosphorus (P4).

Biomolecules like proteins (including enzymes) can consist of thousands or even tens of thousands of atoms in a single molecule.

Insulin, one of the body’s smallest proteins, has the formula C257H383N65O77S6

Physical and Chemical Properties (preview)

While solutions can be separated into constituents by physical means (boiling away a solvent, for example), a molecule can only be broken apart by a chemical change (reaction).

Once chemical bonds of a molecule are broken, they can rearrange to form other compounds (molecules) with very different properties.

For example, liquid water can be separated into hydrogen gas (H2) and oxygen gas (O2) by electric current (hydrolysis).

2 H2O (l) --> 2 H2 (g) + O2 (g)

Hydrogen gas is explosive; oxygen gas is required for fire … but we use water to extinguish some fires.

Sodium (Na) is a soft metal in its elemental state but extremely reactive (i.e., explosive) with water to form a strong base called sodium hydroxide

2 Na (s) + 2 H2O (l) --> 2 NaOH (aq) + H2 (g) + heat

Chlorine gas (Cl2) is extremely toxic and was used as a chemical warfare agent in WWI. It reacts with mucous membranes to form hydrochloric acid.

However, reacting sodium with chlorine makes sodium chloride:

2 Na + Cl2 NaCl

…which you eat every day as table salt.

- Review/try problems 1.11, 1.17, 1.23, and 1.25 at end of chapter.

Physical & Chemical Properties

A physical property is one not associated with a change in chemical composition, such as density, color, hardness, melting/boiling points, and electrical conductivity.

A physical change is a change in a physical property that does not change the chemical makeup of the material.

- Ripping a piece of paper or cutting your hair

- Ice cubes melting into water, or boiling water into steam

- Salt or sugar dissolving in water

A chemical property is defined as the ability of one thing to turn into another, such as flammability, toxicity, acidity, etc.

A chemical change (such as a reaction) produces one or more new materials from the original.

- Burning a piece of paper (combustion reaction)

- Your car rusting (redox reaction)

- Fermentation of sugar into alcohol (gas forming reaction)

- Neutralizing the smell of fish with lemon juice (acid-base reaction)

- Toasting bread or browning meat (Maillard reaction)

- The smell of death (bacterial decomposition)

Chemical reactions can be reversible or irreversible.

Extensive and Intensive Properties

An extensive property is dependent on the amount of material present – such as mass or volume.

An intensive property is independent on the amount of material present – such as the color of your hair, the density of water, or the temperature in the room.

Microscopic properties (physical or chemical) are a result of the chemical structure of an element or compound.

Structure and shape of molecules determine how they interact in bulk with themselves (why is water liquid at room temperature but methane is a gas?) or with other compounds or the human body (such as CO vs CO2 in the body).

Review/try problems 1.27, 1.29, and 1.33 from end of chapter.

Measurements

In science, we make/take measurements – an action that will hopefully provide some useful information about what we’re investigating.

A measurement consists of two parts:

- A number – provides a sense of magnitude and precision (number of significant figures/digits)

- A unit – provides the scale/context of the measurement

One of these without the other is useless. How much acid should I add to the beaker? 4 … 4 what?

How long is this object? 10. 10 what?

Si Units and Derived Units

We use mainly SI units and derived SI units in science.

Common units we will see include Liters (L) or milliliters (mL) for volume; atmospheres (atm) for pressure; and Celsius (°C) for temperature

We also use unit prefixes in measurements because we deal with very large and very small scales (see Table 2.3, pp 28-29). A few examples include:

-

- centi- =1/100th or 0.01

- e.g. 1 meter (m) = 100 centimeters (cm)

- milli- =1/1000th or 0.001

- e.g. 1 liter (L) = 1000 milliliters (mL)

- kilo- =1000

- e.g. 2 kilograms (kg) = 2000 grams (g)

- centi- =1/100th or 0.01

For volume, we typically use liters (L) or milliliters (mL) in lab for liquids and gases, or cubic centimeters (cm3) for solids.

Density is an intensive physical property of a material and defines how much ‘stuff’ is packed into a finite amount of space; the ratio of mass to volume (mass/volume).

The unit of density is grams per milliliter (g/mL) for liquids/gases or grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm3) for solids or liquids. Gases are sometimes expressed in grams per Liter (g/L).

Water has a density of 1.0 g/mL at room temperature. If a material has a density greater than this, it will sink in water; if a material has a density less than this, it will float in water.

Some common materials and their densities…

| State of Matter | Substance | Density | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solids | Wood (Oak) | 0.60 – 0.90 | g/cm³ |

| Iron | 7.87 | g/cm³ | |

| Lead | 11.34 | g/cm³ | |

| Gold | 19.30 | g/cm³ | |

| Liquids | Gasoline | 0.72 – 0.77 | g/cm³ |

| Water (at 4°C) | 1.00 | g/cm³ | |

| Mercury | 13.53 | g/cm³ | |

| Gases (at STP) | Nitrogen | 1.25 | g/L |

| Air | 1.22 | g/L | |

| Radon | 9.73 | g/L |

Common Metric Prefixes in Chemistry

| Prefix | Symbol | Base 10 | Decimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| tera | T | 1012 | 1,000,000,000,000 |

| giga | G | 109 | 1,000,000,000 |

| mega | M | 106 | 1,000,000 |

| kilo | k | 103 | 1,000 |

| deca | da | 101 | 10 |

| (none) | — | 100 | 1 |

| centi | c | 10-2 | 0.01 |

| milli | m | 10-3 | 0.001 |

| micro | μ | 10-6 | 0.000001 |

| nano | n | 10-9 | 0.000000001 |

| pico | p | 10-12 | 0.000000000001 |

| femto | f | 10-15 | 0.000000000000001 |

Review/try problems 1.37 and 1.39 at end of chapter.

Measurement Uncertainty…

Exact Numbers

An exact number is one with no uncertainty, such as a counting number. For example, how many students are in this room? An exact number.

Another type of exact number is a defined quantity, such as 12 inches in 1 foot, or 16 ounces in 1 pound, or 100 centimeters in 1 meter.

All other measurements contain uncertainty, what some may call a precision error. Uncertainty arises from the device used to make the measurement and/or the user’s ability to use the device.

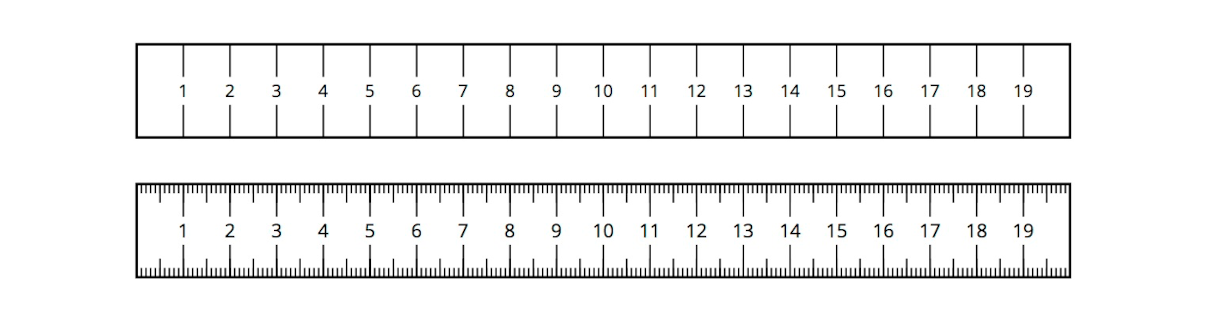

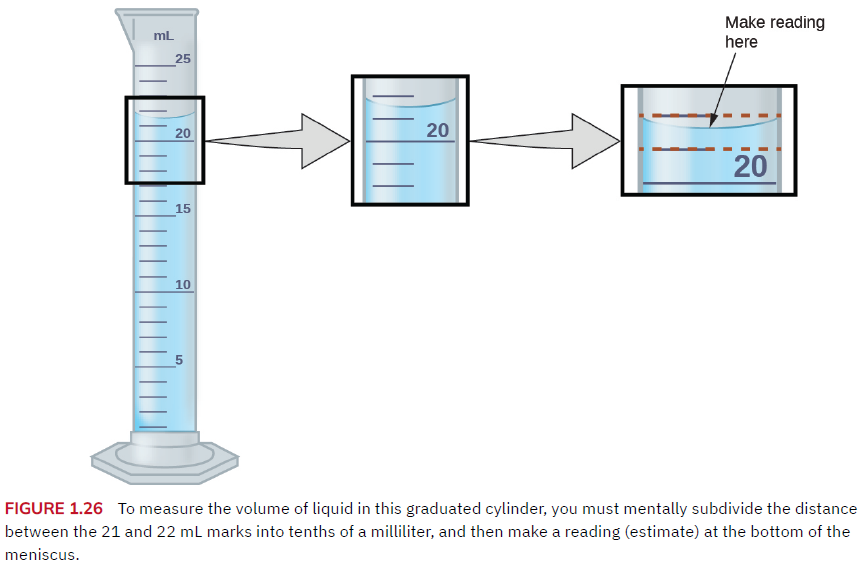

An analog device uses a marked scale, such as a ruler or graduated cylinder. The degree of precision on the device tells us how many digits we can write when measuring with the device.

For example, one metric ruler might have tick marks every centimeter, while a second ruler might have tick marks every millimeter. The second ruler would allow us to write a measurement with more precision (more digits).

A graduated cylinder might have markings for each milliliter, while another might have markings for each 10th of a milliliter.

For analog devices, you can ‘read between the lines’ to add one more digit of precision. The reading above is 21.6 or 21.7 mL.

For digital devices, such as the balances (scales) you’ll use in lab, you can ONLY write down the numbers on the display. But write them ALL down … if the balance reads 1.00 g, then write 1.00 g and NOT 1 g.

All of the numbers are important because it shows the precision of the instrument. A balance in another lab might show 1.0000 g

Whether using analog or digital device, the uncertainty in the measurement is always in the last digit. Uncertainties are sometimes shown as ±. For example, a mass is reported as 2.553 g, the uncertainty of that measurement would be ±0.001 g.

21.7 mL ± 0.1 mL …uncertainty in the last digit.

All digits of a measurement (including the uncertain last digit) are significant. Significant figures (SF) or significant digits tell us the precision of the measurement and must be reported correctly.

How can you tell how many sig figs are in a number (measurement) if you didn’t make it yourself? There are a few rules…

- All numbers between 1 and 9 are significant.

- Zeros are significant if they

- o fall between other numbers (sandwich zeros).

- o Trailing zeros if a decimal point is present.

- Zeros are not significant if they simply determine the power of ten to use in scientific notation, including terminal zeros and zeros to the left of the digits in decimal numbers. (Trailing zeros without a decimal point.)

- Exact or counting numbers have an infinite number of significant figures

The number 1410 has a trailing zero. If we don’t know the precision of the device used to make this measurement, we cannot say with confidence that the trailing zero is significant. Therefore, 1410 would have 3 sig figs.

However, if written as 1410. (with the decimal point), we’d know the device was precise to the ones place, and the trailing zero has a known precision – therefore, 1410. would have 4 sig figs.

In the number 0.00293, the leading zeroes simply show how far from the decimal place the non-zero digits are … they are placeholders and NOT significant … 0.00293 has 3 sig figs.

However, the number 0.002930 tells us that the measuring device has a precision out to 6 decimal places and the trailing zero here is part of that precision (with uncertainty in the last digit, of course). Therefore, 0.002930 has 4 sig figs.

Likewise, a measurement of 12.0 grams shows precision to the tenths place, and 12.0 has 3 sig figs.

Let’s practice a few …

How many sig figs are in each of the following numbers?

|

Example |

Number of Sig Figs |

|

10.4 |

|

|

0.1050 |

|

|

1,000 |

|

|

10.0509 |

|

|

34.00 |

|

|

0.001040 |

1.5 Measurement Uncertainty…

How many sig figs are in each of the following numbers?

|

Example |

Number of Sig Figs |

|

10.4 |

3 SF |

|

0.1050 |

4 SF |

|

1,000 |

1 SF |

|

10.0509 |

6 SF |

|

34.00 |

4 SF |

|

0.001040 |

4 SF |

Rules for Sigs Figs in MATHS

When we use measurements in calculations, there are rules for determining how many sig figs are in the final answer. You can’t have an answer that has more sig figs than the measurements that went into the result

Addition/Subtraction: Guided by the decimal place (precision)

A final answer is rounded to the number of least decimal places in the measurements. Only round at the end!

4.389 + 10.04 – 5.9984 = 8.4306 (raw value)

10.04 only has 2 decimal places, so final value = 8.43

Multiplication/Division – final answer determined by fewest sig figs in a measurement that gave final answer.

Again, carry out the math, then round at the end.

(3.04)*(1.993) / 8.4 = 0.7212761905 (raw value)

8.4 only has 2 SF (the least), so the final answer must be rounded to 2 SF, which = 0.72

Mixed operations – follow the order of operations. You may need to do an intermediate rounding step depending on the order.

For example, (2.40 + 1.889 + 10.1) / 3.7

First, carry out the addition and round by those rules:

2.40 + 1.889 + 10.1 = 14.389 -> rounded to 1 dec place = 14.4

Next, 14.4/3.7 = 3.89189189…. -> rounded to 2 sig figs = 3.9

Final answer is 3.9, with 2 sig figs.

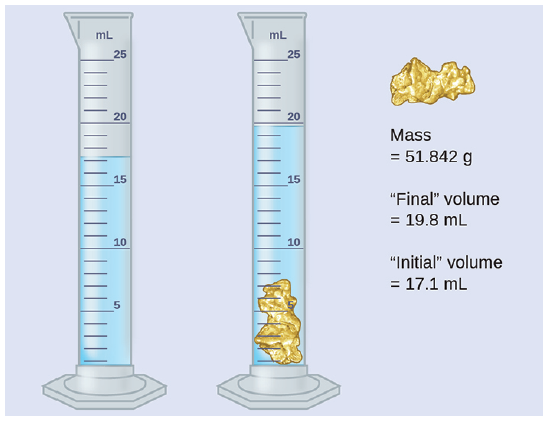

Example

What is the density of the material below?

Density = mass / volume

d = m/V

Vtot = Vfinal – Vinitial

Vtot = 19.8 mL – 17.1 mL

= 2.7 mL

d = 51.842 g / 2.7 mL

= 19.20074074 g/mL

= 19 g/mL (or g/cm3)

Measuring the volume of a small, irregular shaped object is quite accurate by the volume displacement method shown above.

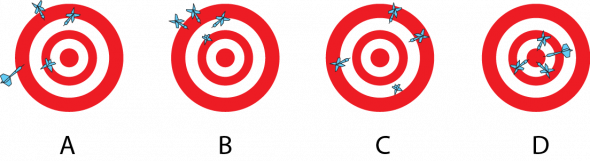

Accuracy vs. Precision

- Accuracy is how close a result is to the true value (or mark)

- Precision is how close results are to each other (i.e., reproducible)

A is not accurate or precise

B is precise but not accurate

C is accurate but not precise

D is accurate and precise

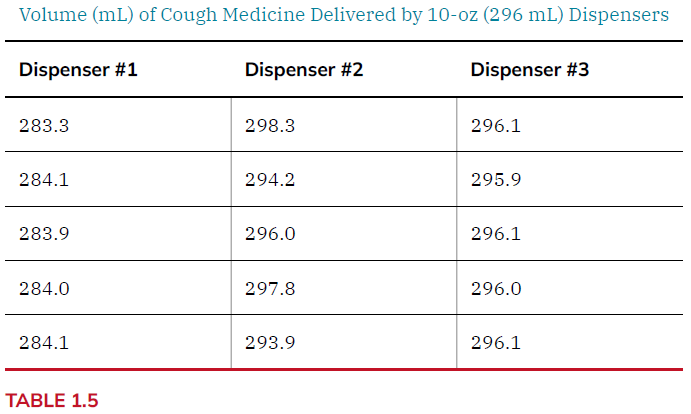

Lets look at an example

| Metric | Dispenser 1 | Dispenser 2 | Dispenser 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | 284.1 mL | 298.3 mL | 296.1 mL |

| Low | 283.3 mL | 293.9 mL | 295.9 mL |

| Range | 0.8 mL | 4.4 mL | 0.2 mL |

| Average | 283.9 mL | 296.0 mL | 296.0 mL |

| Std Dev | 0.3 mL | 2.0 mL | 0.1 mL |

#1 is precise but not accurate; #2 is accurate but no precise; #3 is both

Review/try problems 1.45, 1.47, 1.49, 1.51, and 1.53 at end of chapter.

QUESTIONS ?

Mathematical Treatment of Measurements

While measurements give us meaningful information, we often need to use these date in further calculations to reach a desired result.

This section introduces and practices dimensional analysis (aka factor-label method), which is the process of starting with some value or measurement and converting it into some other value with different units.

A unit conversion factor expresses two equivalent quantities as a ratio that can be used in problems solving. Example include:

- 2.54 cm/1 in

- 1 ft/12 in

- 1000 m/1 km

- °C = K - 273.15

Sig figs are not considered in conversion factors!

Conversion factors display equalities – that is, one part of the ratio (numerator) is equal to the other part of the ratio (denominator) … the units in the numerator and denominator are different, as are the numbers associated with them.

1 ft contains 12 inches … if something is 1 ft in length, it is also 12 inches in length. The conversion factor shows this equality and allows us to convert between two different sets of units, feet and inches.

To convert feet to inches, we start with the initial measurement in feet, then use the conversion factor that links feet and inches in a algebraic equation to end up with inches.

There are many, many conversion factors that allow us to convert between different units, from metric to metric, from metric to English, etc. Later, we’ll see how we can create our own unique conversion factors using balanced chemical reactions.

Temperature Conversions

In healthcare, temperature is a critical vital sign. While Celsius (C) is the standard in most global medical environments, Fahrenheit (F) remains prevalent in U.S. clinical settings, and Kelvin (K) is essential for physiological research and respiratory gas laws.

1. Celsius and Fahrenheit

The relationship between these scales is based on the freezing and boiling points of water. On the Celsius scale, water freezes at 0°C and boils at 100°C; on the Fahrenheit scale, those points are 32°F and 212°F respectively.

To Fahrenheit: Multiply by 1.8 and add 32.

Formula:(°C × 1.8) + 32 = °F

To Celsius: Subtract 32, then divide by 1.8.

Formula:(°F - 32) ÷ 1.8 = °C

Clinical Note: A "normal" adult body temperature of 37°C is exactly 98.6°F.

2. Celsius and Kelvin

The Kelvin scale is an absolute scale. In clinical science, it is most often used when calculating gas volumes or metabolic rates. Because the "size" of a degree is the same for both scales, the conversion is a simple baseline shift.

To Kelvin: Add 273.15 to the Celsius temperature.

Formula: °C + 273.15 = K

Quick Reference Table

| Landmark | Fahrenheit (°F) | Celsius (°C) | Kelvin (K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boiling Point of Water | 212° | 100° | 373.15 |

| Average Body Temp | 98.6° | 37° | 310.15 |

| Freezing Point of Water | 32° | 0° | 273.15 |

A few tips for solving conversion problems…

- After reading the problem, determine the starting point. That is, what measurement are you converting … what are the starting units.

- Next, determine what units you want to end up with.

- Determine the correct conversion factor(s) needed to go from initial units to final units.

- Set up the problem so that starting units will cancel out by multiplication and you’re left only with the final desired units.

- Use your calculator correctly, and use common sense.

Review/try problems 57, 61, 63, 69, 71, 73, 77, 81, 87, 89, 91, 93, 95, and 99.